The over night train journey to London King’s Cross was uneventful, comfortable, but a mind full of thoughts shut out sleep. Thoughts of this decision, thoughts of what he was leaving behind and thoughts of how he was going to manage a new job in a new country, with a language he did not know.

The weather until Carlisle was calm, but as the train sped through the darkness, the wind and rain became more forceful. Standing at the cabin window Jack saw blackness. Only blackness. A black, cold November night. The chill of a loneliness.

Jack’s cabin companion was a 39-year-old gentleman, who was so tall that when he stood, his head almost brushed the cabin roof. With a habit of taking out his pocket watch far more than necessary to check the time, he was an amicable companion for Jack and they chatted together over the last serving of tea and sandwiches from the train guard, around 12 midnight.

He was Dr David Lonie, on his way to London to take up a post at the London Eye Hospital. He was not married, and told Jack ‘I am devoted to helping people Jack’, Dr Lonie said, ‘and I do not have the time a family requires. Besides, I have never met anyone I feel I would want to spend the rest of my life with’. You are lucky Jack’. Jack had shared with David Lonie his story of Kate, how they met, and how they had almost parted for good. It actually shocked Jack himself when he thought that religion could have meant he and Kate could never be together. Jack’s father was a good man, but a staunch Church of Scotland and a Mason at that, who could not concede to his son marrying into ‘the other side’.

‘Could you not have out your foot down Jack’ questioned Dr Lonie.

‘It is just the way it was David’, Jack replied. ‘I could not go against my father’.

‘Then Father died unexpectedly’ continued Jack, ‘and after about 6 months, I knew that I had to make my life with Kate. I feel a disloyalty to Father, but I must go forward with my life. It is wrong to let religion drive life’s course’.

Dr Lonie nodded in agreement but wanted to know how Jack felt going to a country where growing tensions across Imperial Rule were on the increase. Only the year, in1927 had Britain made a grave mistake in sending Lord Simon on a commission to decide India’s political future. The commission had been met with anger and distrust, not least that there were no Indian included in the review. This was just one of many catalysts for increased drive for India Home Rule.

Jack replied, calm as always, and with his own deep respect for all of mankind – ‘David, I am going to do a job, a job to help a country use its own valuable resources to their benefit. I am proud to be British, more so to be a Scot, I am not political. My focus is on doing a job, doing it well, and reaping benefits for my family’.

‘I respect that Jack’ said Dr Lonie, ‘but mark my words, the days of the Empire are numbered’.

Jack was already up and ready to disembark when the train arrived at London King’s Cross. After breakfast at the Station Breakfast room, Jack ensured his luggage was ready for the onward journey to Liverpool where he would finally leave British shores.

Boarding the ship was a tedious and chaotic affair. Thankfully the wind and rain which followed the train to London had abated. Jack was anxious about his trunk. How could he know for sure it had been loaded along with all the other trunks, cargo, crates? The porters seemed to know what they were doing, and everything had been labelled with care.

Keeping his cabin case close by, Jack put his trust in the porters and boarded the ship. His cabin was a single, and was compact. In fact, it was a careful manoeuvre between the narrow bed and the tiny closet to get to the wash hand basin. Leaving his cabin, Jack climbed back to the deck, which was crowded with all kinds of people ready to wave farewell to the crowds of well-wishers below. Men in bonnets, porters in caps, women with children and babes in arms, shouts and orders for the final carts holding cargo bound for India, and destinations en route, and cases and trunks of the passengers on board SS Southampton. Last call for embarking, and final hugs, and tears of departures.

Jack stayed on deck until most others had finally taken their leave to their cabins, the lucky ones at the top of the ship, others deep down in the bowels of the vessel.

It was Sat 17th November, 1928. 12 noon. As the horizon of home shores grew further and further away, Jack turned towards the stairs, to go settle into his cabin. As he puts his hand into his jacket pocket he felt a small soft pouch. On opening it, he found a small silver medallion, and recognised it as a St Christopher. Kate must have put it in his pocket before he had left home for the train. Her blessing. Jack felt relief. Brushing a tear away, he stepped on, ready to take on this new chapter of what would be a life well lived.

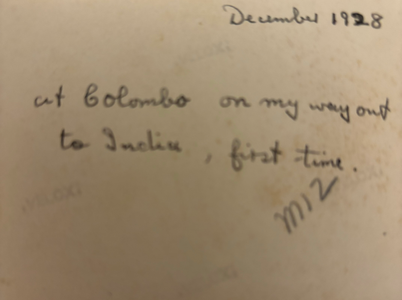

After 30 days at sea, and 2 days via Indian rail, Jack finally arrived in Calcutta.

On Tuesday 25th December, 1928, Jack started work at the American owned Ludlow Jute mill on the banks of the River Hoogly, at Chengail, a small village 25 miles from central Calcutta.

Comments